Manchester cellar dwellings - a Victorian housing scandal

In 1850s Manchester, more than 16,000 people lived underground in cellars

As families flooded into Victorian Manchester in search of work, the city’s landlords saw a unique opportunity.

They turned the cellars of old houses that had been used as workshops and storage spaces into rented “homes”.

By 1854, more than 16,000 people in Manchester were living underground in 4,600 cellars. Six years later, the number had jumped to over 17,000.

The landlords packed them in by further splitting the cellars into two rooms, which could each house ten or 12 people.

Each had a fireplace, which shrouded the rooms in toxic smoke. If the cellar was below a privy, human waste would leach down the walls.

Some only had one door and there were reports that others were accessed from trap doors in floors or subterranean passageways.

Few outsiders were brave enough to visit the people living below ground and take a look at their living conditions.

But the journalist Angus Reach described the scene he found in what he described as “the worst cellar in all Manchester” during a visit to Angel Meadow with a police officer.

“The air was thick with damp and stench,” he wrote. “The vaults were mere subterranean holes, utterly without light.

“The flicker of the candle showed their grimy walls, reeking with foetid damp, which trickled in greasy drops down to the floor.”

Reach wrote of how beds were huddled in every corner – some of them on frames and some on the floor.

“In one of these a man was lying dressed, and beside him slept a well-grown calf,” he wrote.

Sanitary inspectors campaigned for the cellars to be shut down, with a newspaper called The Builder reporting that these underground “caves” were little better for sleeping in than burial vaults.

It told how babies were born in these cellars and how they struggled for life, with half of all children in the district dying before the age of five.

By 1861, Manchester’s buildings and sanitary committee had shut down 340 of the worst cellars in the city.

But within five years, the closure rate had dropped and there were still more than 3,000 cellars in the city.

Inspectors even estimated it would take more than a century, until 1965, to close them all.

They found that some that had been shut were quietly being opened again by the landlords, with new tenants being moved in.

The landlords then launched a public campaign, forming the Manchester Property Owners’ Association, and began claiming that closing cellars caused overcrowding above ground.

The real scandal though was to be found within the walls of Manchester’s town hall, which then stood on King Street.

It turned out that Alderman Boardman, the chairman of the sanitary committee, was a member of an organisation that was campaigning against the closures.

He personally owned 30 cellars in Angel Meadow.

But anyone in doubt about the horrors of Manchester’s underworld had only to read Reach’s account of his visit to Angel Meadow.

Going deeper into the cellars, past a drunken man “roaring for help” in a makeshift bed, Reach made a shocking discovery.

“‘What’s this you have been doing?’ said my conductor to the landlady, stooping down and examining the lower part of one of the walls.

“I joined him, and saw that a sort of hole or shallow cave, about six feet long, two deep, and a little more than one high, had been scooped out through the wall into the earth on the outside of the foundation, there being probably some yard on the other side.

“In this hole or earthen cupboard, there was stretched, upon a scanty litter of foul-smelling straw, a human being — an old man.

“As he lay on his back, his face was not too inches beneath the roof — so to speak — of the hole.

“‘He’s a poor old boy,’ said the landlady, in a tone of deprecation, ‘and if we didn’t let him crawl in there he would have to sleep in the streets’.

“I turned away,” Reach wrote, “and was glad when I found myself breathing such comparatively fresh air as can be found in Angel Meadow, Manchester.”

Return to Angel Meadow

I hope you found this weekend’s newsletter interesting. I’ve written previously about how my own family lived in cellars when they arrived in Manchester from Ireland in the 1860s.

If you want to read about how that discovery led me to write my Angel Meadow book, here’s an interview I did this week with the historian and genealogist Emma Jolly.

It’s the first time I’ve spoken at any length about writing it and the difficulties in researching the district’s most harrowing stories.

Have a good weekend.

Hiya Dean,

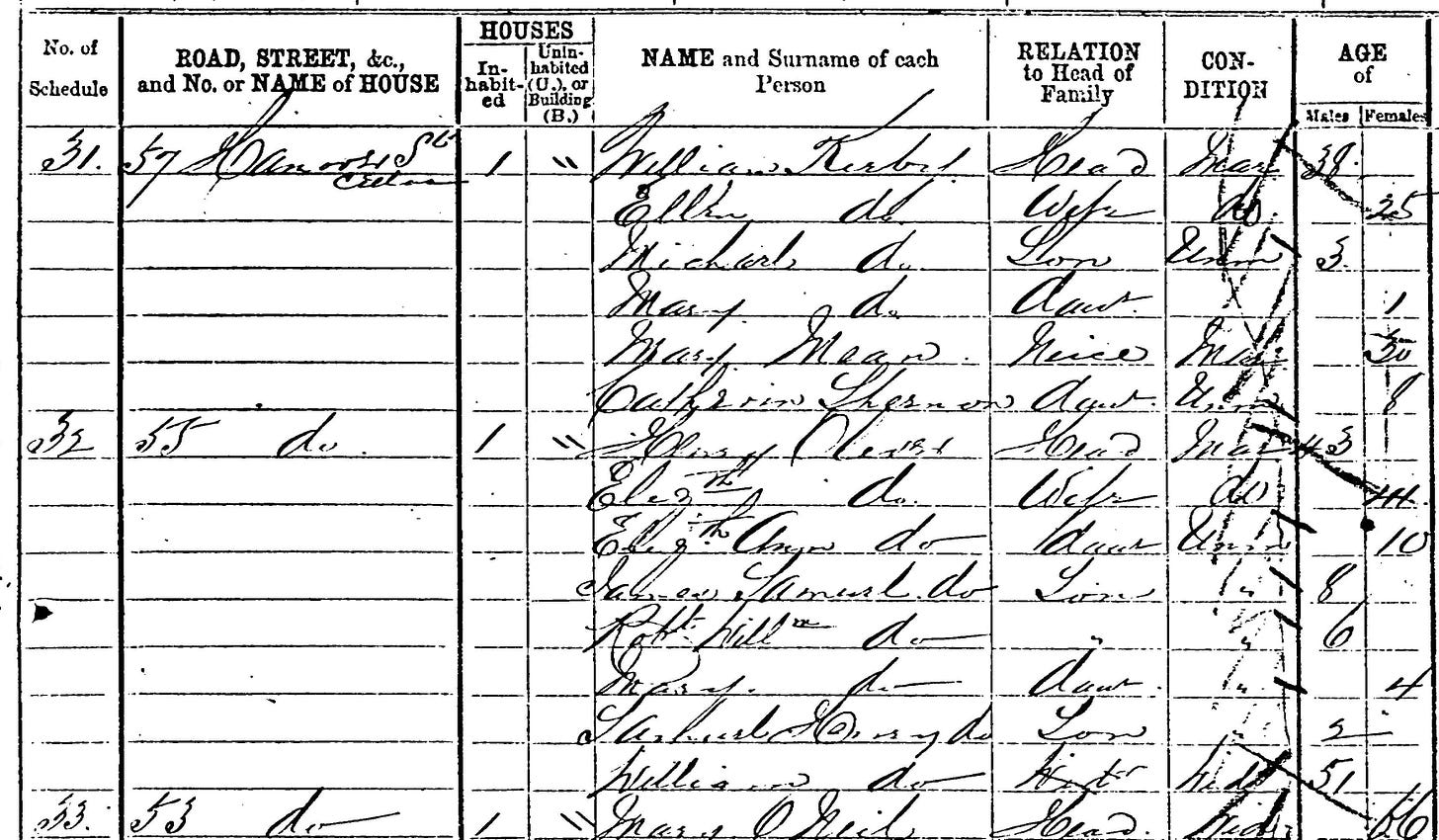

How can you tell from the census return if someone was living in a cellar ? Is it clearly marked ?

I looked through some of my relatives census returns from 1851-1871 and all I can see is the house numbers no mention of cellars ?

I also wondered about courts, (I have family who lived in Thompsons court 1851.)

Why were they called courts ? Was it because it was a dead end street or they were not on a road/street ?

Just looked it's a written interview, I'll sit down with a cuppa later.