Finding George: A Remembrance Sunday Story

A journey to find one soldier who never returned home from the First World War

On the border of Beswick and Openshaw in east Manchester, there is no longer any sign of the neat terraced row that once formed Mitchell Street.

Demolished decades ago, a tyre garage and a scrap metal yard now stand in their place near the concrete carriageway of Alan Turing Way.

But inside one of those houses in August 1914, a family was quietly contemplating the news that Britain had declared war on Germany.

No.1 Mitchell Street was the home of my great-grandfather’s brother George Grindley, his wife Pollie and their daughter Alice, who was less than a year old.

Soon George would be hugging his family for a final time and joining the long line of Manchester men called to fight in the trenches of northern France.

Pollie was expecting their second daughter, Elizabeth, who would be born while he was abroad.

Researching my family tree and finding George’s war records online, I became captivated by his story.

Early one morning, after a lot of planning, I pulled up my car as close as I could to where Mitchell Street had stood and paused for a long moment.

Then I set off on a 400 mile journey to find out what happened to him.

A few days later, I was standing in the woods at Acheux-en-Amiénois a few miles north of the town of Albert on the Somme.

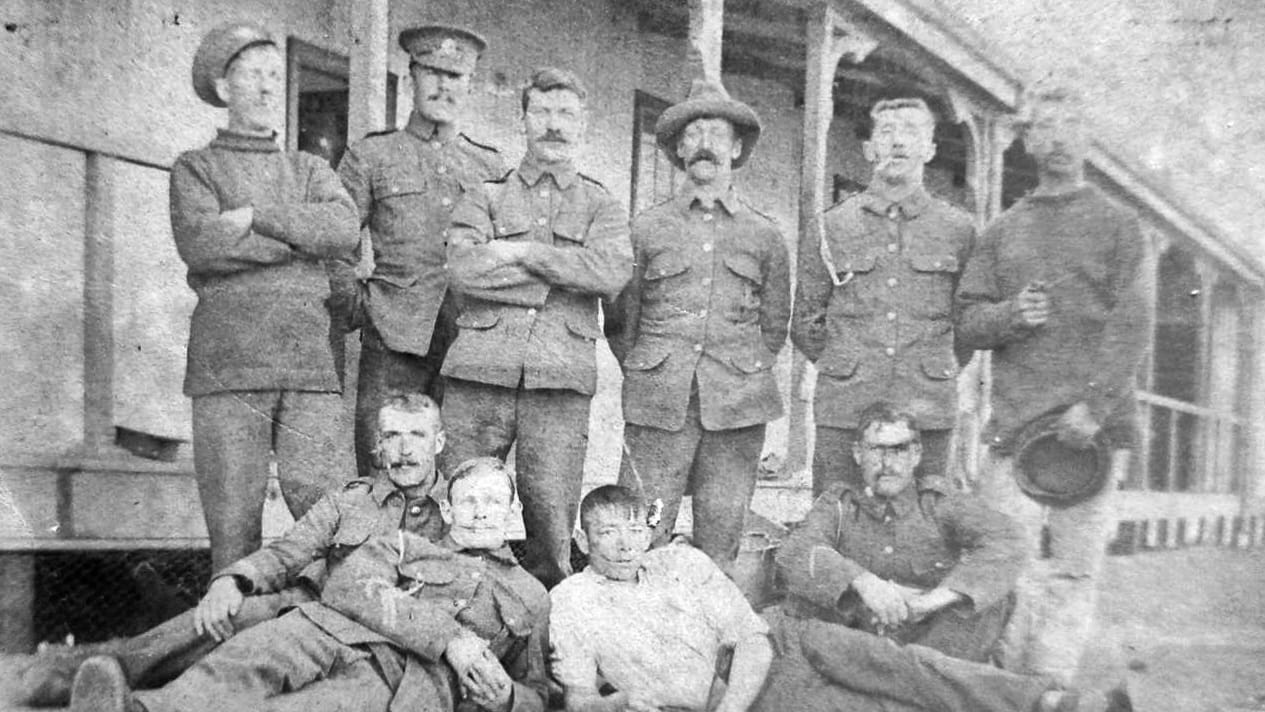

George was 31 when he arrived in those woods in 1916, with the war diaries of his battalion — the 2nd South Lancashire — showing they camped under the same beech trees after being taken to the front by train.

“The noise is terrific, and the sky is lit up with the flashes of shells and guns,” a second lieutenant named Harry Cottrell wrote to his mother, Agnes, that night.

“We are are going into our trenches in a day or two, however, don’t worry as it is quite a simple thing now.”

Over the next week, I followed George up the line, using maps and the war diaries to trace the battalion’s route through the communication trenches to Mouquet Farm, where George saw his first action of the war.

A former Dragoon Guard, he had previously served in India and South Africa, but the conditions here at what is now a quiet farmstead were unlike anything the experienced soldier could have ever imagined.

In heavy rain, defending trenches that were little more than a line of shell holes, the men were hit by two days of heavy German shelling that churned the living bodies of wounded soldiers into the mud.

Among those who died was Harry Cottrell, aged just 18, who had written home days earlier.

Ration parties bringing up food from rear went missing and some of the 16 Lancashire lads who were killed had to be buried in shallow graves that were never found again.

Luckily, a plan to send the battalion over the top was cancelled just in time.

I learned that George fought on until 21 October, three months after his daughter Elizabeth was born back in Openshaw.

It was then that the fateful order to attack finally came.

As dawn broke that day, the battalion was waiting uneasily after a frosty night at the top of a ridge in a former German stronghold known as Stuff Redoubt.

At exactly 12.06pm, whistles blew and the men poured over the top and charged down a slope towards the German 5th Ersatz Division.

Standing in the same field, I closed my eyes and tried to imagine the Lancashire men approaching.

Numbers of them were dying beneath the creeping barrage of British guns that moved forward too slowly as they went forward.

After they took their objective in just 15 minutes, the German artillery opened up on their own defences while snippers fired at the British uniforms.

Somewhere here, in that maelstrom of bullets and burning fragments of shrapnel, George fell to the ground severely wounded.

He was carried off the field by German prisoners and taken by ambulance to a field hospital in the village of Bouzincourt.

Later that day, as Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig was sending his “hearty congratulations” to the battalion commander, George died.

He lies buried in a the village cemetery among his fellow soldiers, whose graves stand in straight ranks next to a farm where French cows watch visitors from over a wall.

In a heart-breaking note that can be found in George’s military records, Pollie later wrote to the Army from their home in Mitchell Street: “I have received no effects whatsoever — only his identification disc.”

Pollie wrote a poem that that says everything about the loss suffered in that one house in Manchester. It was published in George’s death notice in the Manchester Evening News.

He has gone from his two little girls and his wife,

Whom he willingly toiled for and loved all his life;

Somewhere abroad in a soldier’s grave,

Lies my dear husband among the brave.

George’s great-granddaughter Dionne Spence, who makes an annual pilgrimage from Manchester to his grave, says his memory will live on.

“I travel to his grave every year to pay my respects,” Dionne says.

“The cemetery is in a very sleepy village and it is beautifully maintained and cared for. It’s overlooked by farmers’ fields.

“Every time I go, as soon as I walk through the gate, I feel a sense of peace. I get quite emotional being reunited with my great-grandfather and I wonder he’s proud of me for being there.

“Knowing his story makes me proud, and sharing it with my family means that his legacy and memory will always be held close.”

Research your First World War ancestors on Armistice weekend

If you haven’t searched for your First World War ancestors before, it’s easy to do and there are lots of records available online which you can search today.

Find My Past is making its military records, including soldiers’ personnel files, free to use this Armistice weekend if you register with the site. Check out the link here.

Another good source is the National Archives, which has records you can download including battalion war diaries and medal index cards. Click here.

If you want to trace places mentioned in the diaries, there is a collection of British trench maps on the National Library of Scotland website here.

The Imperial War Museum has a collection of 11 photographs including many from 1914-18 here.

To search for soldiers who died in the First World War and their grave records, visit the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website here.

Detail’s of Manchester’s Remembrance Sunday service can be found here and Salford’s here.

It’d be good to hear how you get on with your research, or if I can help, drop me a line at dean@mancunianhistorian.uk.

Have a peaceful weekend.

A very moving tribute Dean.