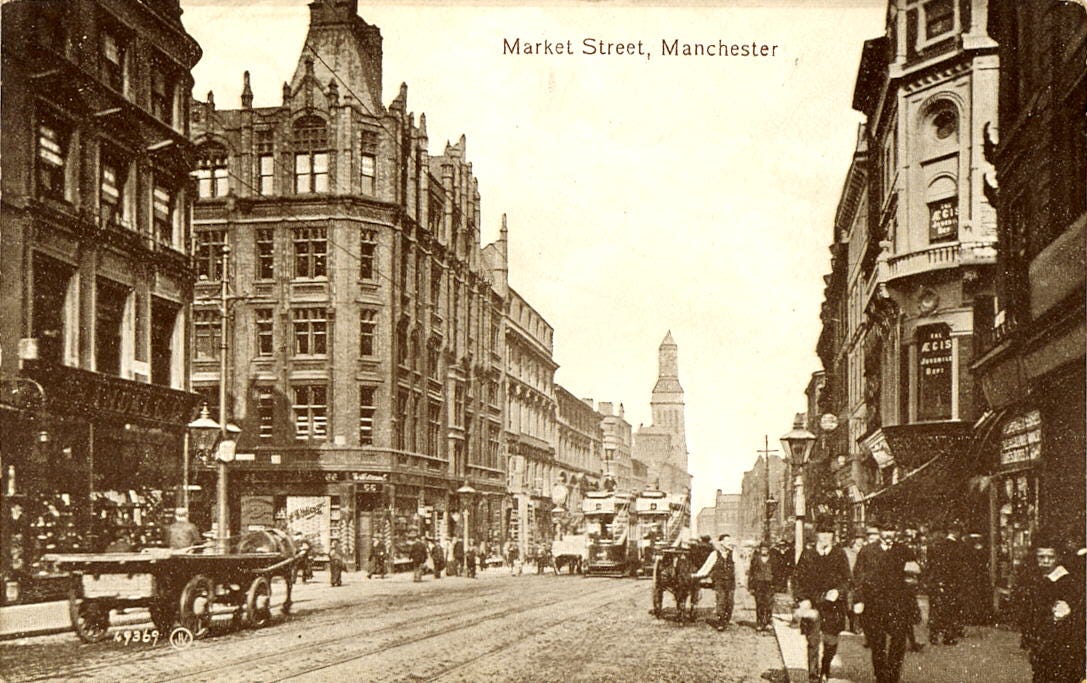

Manchester: Your city, your history

Manchester is your city and its story is yours to tell. So why not take part in the telling?

The story of Manchester’s role in the creation of the modern world is so well known it is easy to think the history of the city and its people has long been etched into stone.

It was the world’s first industrial city — the beating heart of a cotton empire that stretched around the globe. It was also the…