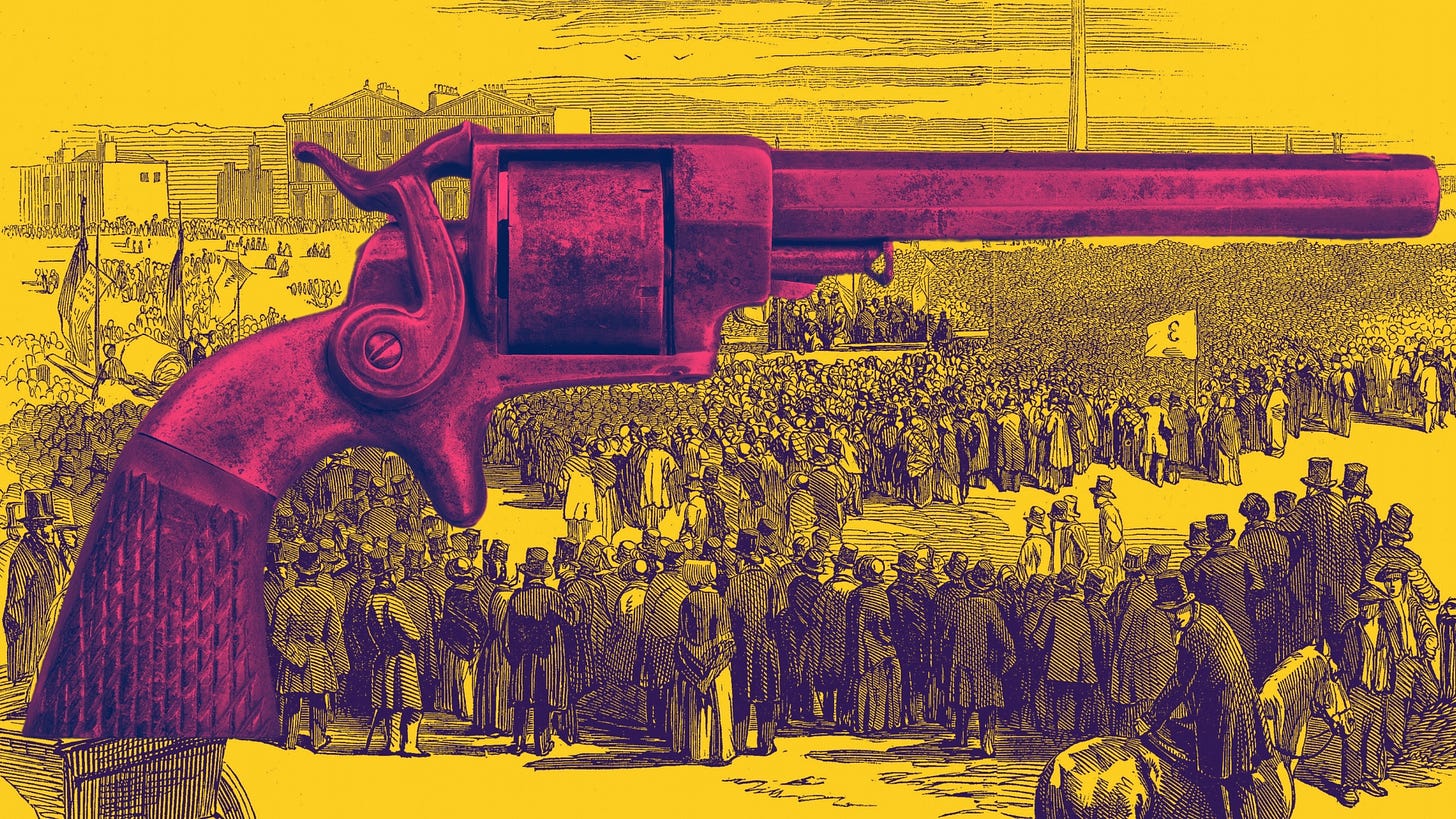

Guns and nettle beer

James Downey was a cobbler by day and a Chartist arms dealer by night

James Downey the cobbler was a busy man.

His job was to repair the mill workers’ clogs that clacked on the cobbles before the dawn whistle marked the start of their daily grind.

The weavers liked coming into his shop at the top of Gould Street. Downey gave them fizzy pop and nettle beer.

But at night he had a side hustle that of late was keeping his candle…