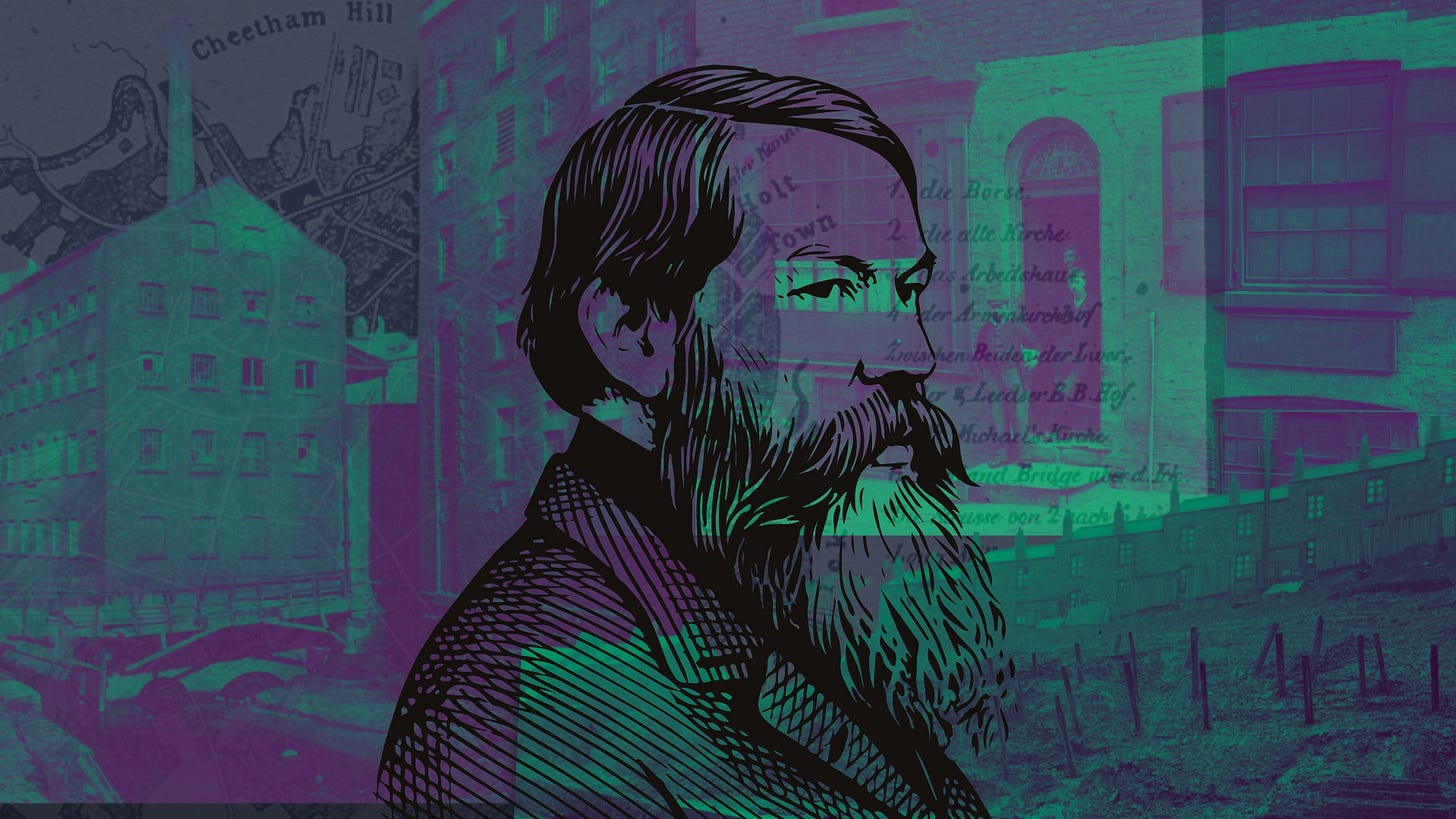

Finding Mr Engels: Part 3

It's 1844 and a well-dressed man is walking through the streets of the world's first industrial city. The cotton looms are thumping like a heartbeat.

It’s 1844 and a well-dressed man is walking through the streets of Manchester.

His ears are tuned in to the music of the world’s first industrial city:

The flying shuttles thumping across the cotton looms like a heartbeat.

The click-clack of the clogs on the cobbles.

The man spins left off the street …