The killer of little mule spinners

Reaching over the machines to repair broken threads of cotton, the mule spinners of Manchester and Lancashire were falling victim to a silent killer

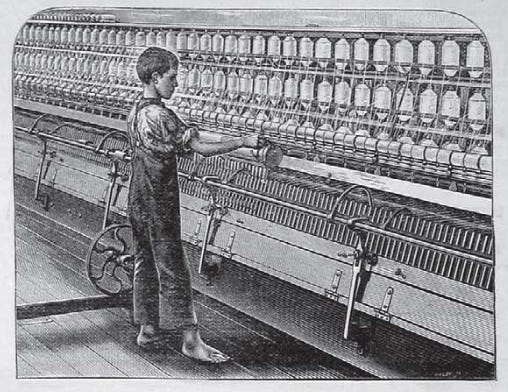

The men and boys who oversaw the spinning mules were as closely knit in their work as the threads they spun.

Moving back and forth throughout their shift in the cotton mills, they always operated in teams of three.

Two lads — a little piecer and a big piecer. The man, known as the minder, made sure they didn’t get trapped by the machines.

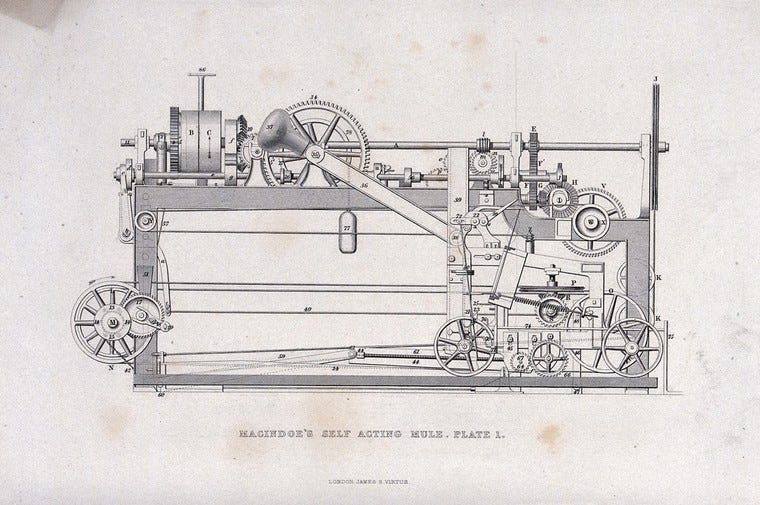

The piecers had just seconds to fix the snapped pieces of yarn before the entire mule — a 150ft-wide carriage of 1,000 spindles — lunged forward five feet.

Keeping safe from the obvious danger required real skill and co-ordination amid the noise and heat of the spinning room.

You had to put all your weight on your left foot and throw your right leg out behind.

Then lean in and twist the threads with the thumb and forefinger of your left hand.

Finally, straighten up and step away — a pirouette they performed hundreds of times a day.

But each time the boys leaned over the carriage’s rail and twisted those threads, they were facing a hidden danger.

The mineral oils that were used to lubricate the mule were giving them cancer.

Dear reader — If you’ve been enjoying the newsletter, please consider subscribing using the button below. It genuinely makes a difference in helping me keep this newsletter going. Check out your subscription options here — you can unsubscribe any time, with one click.

Mule spinners’ cancer, as it became known, was first identified by doctors here in Manchester in 1887.

By then the oils, usually derived from shale, had been in use for around 35 years — giving cancer to an untold number of boys and men.

While the piecers were working, the mule carriage silently threw out a fine mist of oil at the height of the groin.

And to keep the mules efficent, the mill overseers were dousing the machines with that oil several times a day.

Smaller men and boys who had to stretch and lean more over the rail were at greater risk.

The cancer started as a warty ulcer on the skin of the outside of the left testicle — the side on which the piecers leaned against the mule.

It could be removed with surgery in the early stages. But once it had spread to the internal organs, it was too late.

By 1900 there was a shockingly high number of cases of former mule spinners dying from the cancer.

But, as late as the 1920s, some doctors who worked with the cotton industry denied there was a problem.

Dr Vernon Davies, an MP, wrote: “I was certifying surgeon for Shaw [in Oldham] for 22 years, and have never seen scrotal cancer in spinners.”

Some blamed a lack of cleanliness among the workers.

Others said it was caused by the tightening of their overalls as the piecers stretched over the machines.

A doctor named John Brown, a former medical officer for Bacup in Lancashire, claimed in 1924 he had never heard of a single case in his own district.

“All the information I have been able to collect goes to prove that this [disease] is very infrequently met even at the present day.”

But the factory overlords were worried — less about the health of their workers perhaps than about the potential for mass compensation claims.

At that time there were 20,000 spinners in the region.

The Operative Spinners’ Amalgamation said they already had 80 cancer cases on their books.

At a compensation court in Ashton-under-Lyne, a judge heard that half of the scrotal cancer cases treated at Manchester Royal Infirmary were mule spinners.

The son of one spinner across the Pennines in Yorkshire told an inquest into his death from cancer: “His trousers got oily, but were washed my by mother, and then, when they became dirty again, they were thrown away.

“After work, if he was going out, he would change his trousers, but if not he would keep on his work clothes.”

It was not until 1925 that the Home Office finally launched an inquiry.

The investigation discovered that the mortality rate among cotton spinners aged 25 to 35 was 14 times greater than the general population.

By the ages of 45 to 55, it was sixty times as great and by the ages of 55 to 75 it was a hundred times greater.

In Oldham, which alone had more than 8,000 spinners, 229 cases were found.

A study even worked out that the death rate in the town was rising as the cotton industry boomed in the 1920s as more spinners were being employed.

The Home Office inquiry confirmed that mineral oils were the cause and recommended efforts be made to replace them with non-carcinogens.

Splash guards were also ordered to be placed on the machines to prevent oil from spraying on the workers’ trousers.

Mule spinners over 30 would be required to have medical checks every four months.

But as late as 1941, a doctor named Brockbank wrote in the British Medical Journal how he had seen more than 150 cases including some that were “hopelessly neglected”.

From 1923 to 1939 there were more than 350 deaths and, even as the Second World War was starting, factory inspectors said they had identified another 52 cases.

They included a Dukinfield man named George Harrop, who was just 56 when he died.

He had worked at one of the biggest mills in Ancoats for more than a decade before the cancer forced him to give up work in 1926.

A five-paragraph story in the industry’s newspaper, the Cotton Factory Times, noted that an inquest had recorded a verdict of death from “misadventure”.

“He was an extremely good workman,” a solicitor for Mr Harrop’s employers told the coroner.

“They very much regretted his incapacity and the long illness from which he suffered and resulted in his death.”

But for hard-working Mr Harrop, the regrets of his employers came far too late.

Cotton towns ancestry

I hope you found this story interesting.

I still find it amazing that so little is known about the effects of an industry that dominated people’s lives in our area for well over a century.

If you’re looking to find out more about your cotton industry ancestors, please do check out my professional family history site www.cottontownsancestry.com.

I’ve recently revamped the site to better reflect that my work covers not just Manchester but the mill towns of Greater Manchester and Lancashire.

There’s a link on the site where you can book a free family history consultation with no obligation to commission me for any work.

Have a good weekend.

A very interesting story. Thanks for sharing.

Superb article Dean. So much of the mill industry was driven by politics, I wonder who the doctors were protecting, certainly not the workers.

I love your updated website - fabulous!